Outlining Italianness in Study Abroad Programs in Italy: A Comparison Between American and Italian Students Ph.D., M.A., Prof. Piero Ianniello*

University of New Haven, Italy

*Correspondence to: Piero Ianniello

Citation: Ianniello P (2023) Outlining Italianness in Study Abroad Programs in Italy: A Comparison Between American and Italian Students. Sci Academique 4(1): 72-82

Received: 19 May, 2023; Accepted: 20 June, 2023; Publication: 28 June, 2023

Abstract

This article is contextualized in the field of the Study Abroad Programs, that have been widespread in Italy for several decades. It aims at outlining the idea of Italian-ness, as an enrichment of the cultural capital of each students that take the experience abroad. For this purpose, the article first examines the diffusion of the Study Abroad Programs in Italy (about 145 programs), and then proceeds presenting the outcomes of three surveys aimed at outlining the idea of Italian-ness among American students as they arrive in Italy for the first time (expected or imagined Italian-ness), American students who already had an experience in Study Abroad programs (experienced Italian-ness as foreigners) and Italian students (experienced Italian-ness as locals). I will conclude the article analysing the results and proving that the more a student is immersed, the more his idea of the local culture will be closer to the locals’ one. Thus, it is up to the Study Abroad Programs providing the right context for an effective life changing (or identity changing) experience, which leads to an improving of the student’s cultural capital.

Keywords: Italian-ness; American Study Abroad; American higher education

Introduction

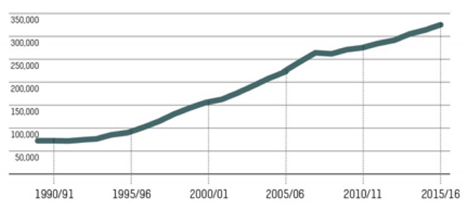

In American universities Study Abroad programs represent a source of great pride, because they are appreciated by students and also because it represents an attractive point for potential future students. According to an estimation provided by the IIE, more than 300.000 university students from the U.S. study abroad each year. In 2015/2016 325,399 American students studied abroad, with an increase of 3.8% compared to the previous academic year (Open Doors 2017). American students attend 2.600 programs in 129 different countries. The most commonly attended destination for Study Abroad students is the UK, closely followed by Italy. It may be surprising that American students choose Italy as the second favorite destination for their study abroad.

Figure 1: US Study Abroad Students 1989/90 – 2015/16. Statistics provided by IIE 2017.

According to many scholars, American ruling class was in search of “[…] the origins of the values of democracy, freedom, rational thought, individualism[1], the scientific method and the capacity for critical reflection on their lives which are at the base of their way of living, their political thought”. (Ricciardelli 2017: 18) Italian Renaissance, for its civic values, is recognized as “an essential paradigm for the formation of the modern western world” (Ricciardelli 2017: 19). Also Educating in Paradise reveals that the historic-artistic and cultural heritage is “the chief element in the attractiveness of Italy among North American university students abroad” (Ricciardelli 2017: 154).

One of the many providers of study abroad programs advertises studying in Italy in this way: “Heart of the Roman Empire, birthplace of the Renaissance, and home of the Vatican and Roman Catholic Church, Italy has made innumerable contributions to Western Civilization. Though its history and landmarks are familiar to us from books and movies, there is no substitute for the first time you stand in front of the Colosseum where countless others have gone before you over two millennia. Spend a summer, January term, semester or academic year studying abroad with AIFS in Rome, Florence, or the Italian Alps and you may just scratch the surface of what this timeless nation has to offer” (AIFS website). One more reason because Americans students choose Italy may reside in the Italian origin many American can claim. “For about ¼ of the participants in the programs, the experience of studying in Italy also represents an occasion for deeper knowledge of one’s own origin and the traditions linked to it” (Schneider 2013:126) Finally, Rae Knopik finds that: “The first reason seems to have to do with what Italian-based programs provide. The country offers a disproportionately large selections of courses in humanities and social studies when compared to other areas of study. Among other benefits, many students also view study abroad as a resume builder” (Knopik 2016: 16).

Europe hosts more than the 50% of the students studying abroad. Italy, as said, hosts about 11% of the North American students. Currently, Rome is still the city hosting the highest number of Study Abroad programs (51 programs, 35% of the total), followed by Firenze (41 programs, 28% of the total)[2]. As for students, these two cities enroll 80% of the total in Italy.

Study abroad in Italy

Although a few programs are very old, many of them were established in Italy in the last 25 years. In 2013 about one third of the programs were found to be less than 10 years old. The youngest ones are part of a phenomenon that Schneider calls “study abroad boom”, occurred from 2002 and 2012 (Schneider 2013: 10). According to many workers in the field, this boom is a direct consequence of a law passed by the Italian government in 1999 (art. 2 of law n. 4/1999), the so-called ‘Barile Law’. With this law Study Abroad Programs were recognized with the no-profit status (off shore), just like Italian Universities, offering them tax exemption[3]. Most of the programs established in Italy enroll less than 100 students per academic year, whereas one third of the programs enroll less than 50 students. Schneider estimates that altogether study abroad programs have populated Italy with approximately 300,000 students since 1978. In general, the smaller number of students corresponds to the newer programs. Schneider also notes that the smaller number might be “a sign of the learning experience’s high quality, considering that students get more individual attention, are more motivated to interact and to be exposed to the new culture” (Schneider 2013: 13).

Outlining Italian-ness: American students newly arrived in Italy

To measure the idea of Italian-ness from the point of view of American students today, I have conducted a survey (Survey 1 – before) on 35 students newly arrived in Italy, and thus had a vision of Italy that was likely preconceived and influenced by mass media. Questions of the survey were carefully chosen for the purpose of the research. I have opted for open ended questions, so to avoid influencing respondents’ answers in any way (this kind of questions. are unbiased, do not show to respondents the possible expectations of what the researcher might be looking for). Respondents were asked to write, without prompt, five salient characteristics that according to them represented Italians. The answers were then divided into categories corresponding to semantic areas that seemed, in our opinion, to include the adjectives listed below. The number that appears beside the name of each category relates to the quantity of adjectives present in that category. The number beside each adjective refers to the number of times that adjective appeared in the students’ answers. The results of the survey are as follows. Social behaviours were mentioned 51 times:

| Social Behaviours: total 51 times | |

| Noisy | 14 |

| Gesticulate | 9 |

| Speak a lot | 6 |

| Smoke | 5 |

| Lack of personal space | 3 |

| Speak fast | 3 |

| Sophisticated and good mannered | 2 |

| Raise their voice at the end of each sentence | 1 |

| Stare | 1 |

| Move around in small groups | 1 |

| Kiss | 1 |

Table 1: Survey 1 (before) – Social behaviour.

Traits referring to Character were mentioned 50 times:

| Character: total 50 times | |

| Friendly/kind/affectionate | 14 |

| Passionate (4) Emotional (2) Aggressive (1) | 7 |

| Relaxed | 6 |

| Energetic | 5 |

| Respectful/polite | 5 |

| Welcoming | 3 |

| Expressive | 2 |

| Direct | 2 |

| Self confident | 2 |

| Generous | 2 |

| Honest | 1 |

| Open to new experiences | 1 |

Table 2: Survey 1 (before) – Character.

Appearance was mentioned 15 times:

| Appearance: total 15 times | |

| Tanned complexion | 6 |

| Dark hair | 3 |

| Greasy hair | 2 |

| Good looking | 2 |

| Modern haircut | 1 |

| Tall | 1 |

Table 3: Survey 1(before) – Appearance.

Unavoidably, food was mentioned as one of the markers which best characterizes Italians in the American students’ eyes. Food was mentioned 14 times:

| Food: total 14 times | |

| Eat a lot | 7 |

| Drink coffee | 2 |

| Love pizza | 2 |

| Love pasta | 1 |

| Good cook | 1 |

| Run an Italian restaurant | 1 |

Table 4: Survey 1 (before) – Food.

Health conduct was another interesting characteristic noted by students. Health conduct was mentioned 7 times:

| Health conduct: total 7 times | |

| Walk a lot | 3 |

| Night owls | 2 |

| Lead a healthy life | 1 |

| Ride a bike | 1 |

Table 5: Survey 1 (before) – Health conduct.

Finally, clothing was mentioned 19 times:

| Clothing: total 19 times | |

| Fashionable | 14 |

| Have a leather pursue | 2 |

| Unbutton their shirts | 1 |

| Wear shirts with collar | 1 |

| Wear jeans | 1 |

Table 6: Survey 1 (before) – Clothing.

It may be interesting to note how most of the observations referred to social behaviours and traits that normally describe the character of a person, and that they appear in the students’ descriptions as a sort of character of the nation. We are probably faced with an interpretation of specific social and cultural behaviours that are perceived by certain cultures as a symptom of displays of affection, openness, amiability, etc., aided of course by a solid cinematographic and advertising propaganda that leans in the same direction.

Italian-ness among American students with Italian experience

The same survey (Survey 1 – after) was then conducted on 24 students that previously spent a semester in Prato and were now back home in the United States. The results of the survey are as follows.

| Social behaviours: total 30 times | |

| Gesticulate | 9 |

| Speak loud | 5 |

| Give importance to arts and culture | 5 |

| Family-bond | 4 |

| Love soccer | 3 |

| Very close when talk | 1 |

| Give importance to religion | 1 |

| Strike frequently | 1 |

| Smoke | 1 |

Table 7: Survey 1 (after) – Social behavior.

| Character: total 7 times | |

| Relaxed and lead a calm life | 3 |

| Happy | 2 |

| Hospitable | 1 |

| Warm | 1 |

Table 8: Survey 1 (after) – Character.

Appearance was mentioned 6 times:

| Appearance: total 6 times | |

| Fashionable | 2 |

| Fascinating | 1 |

| Elegant | 1 |

| Beautiful women | 1 |

| Smell | 1 |

Table 9: Survey 1 (after) – Appearance.

Finally, food was again mentioned:

| Food: total 13 times | |

| Give importance to the quality of food | 11 |

| Love wine | 2 |

Table 10: Survey 1 (after) – Food.

ITALIAN-ness among Italian peers

I have been conducting the same survey among 32 Italian students, in order to define the identity markers that compose the emic category of ascription to Italian-ness within a group of Italian peers, so that independent age variable can be factored out as much as possible (Survey 2 – Italian peers).

The results

| Food: total 35 times | |

| Give importance to food in general | 13 |

| Give importance to good (healthy) food | 8 |

| Love pasta | 7 |

| Love pizza | 6 |

| Love wine | 1 |

Table 11: Survey 2 (Italian peers) – Food.

Social behavior is still one of the most mentioned markers. Besides gesticulation, which must be an old habit together with swearing and speaking loud, Italians also claim that they, as Italians, are part of a broader artistic and cultural heritage, which is often enjoyed and shared within the family or in cultural associations, whereas the participation of foreign students in these contexts is quite scarce. Soccer is by far the most loved sport, even though mainly by male students. Many of them practice it and support specific Italian teams, still being informed about the international arena (mostly European).

| Social Behaviour’s: total 31 times | |

| Gesticulate | 11 |

| Give importance to culture and art | 6 |

| Give importance to soccer | 6 |

| Swear | 3 |

| Speak loud | 2 |

| Kiss | 2 |

| Are always late | 1 |

Table 12: Survey 2 (Italian peers) – Social behaviors.

A friendly, sociable and open (literally: ‘solar’, ‘bright’) attitude towards the other is what Italian youngsters ascribe to themselves as the most important characterization.

| Character: total 22 times | |

| Warm | 8 |

| Sociable and friendly | 6 |

| Authentic | 3 |

| Energetic | 2 |

| Family-bound | 1 |

| Tradition-devoted | 1 |

| Stingy | 1 |

Table 13: Survey 2 (Italian peers) – Character.

Language is still characterized by one of the most highlighting markers. Interviewees feel they have a national identity because they speak a supranational language. As known, Italy is still characterized by the presence of many dialects, but actually only one student mentioned it.

| Language: total 18 times | |

| Speak Italian language | 17 |

| Speak an Italian dialect | 1 |

Table 14: Survey 2 (Italian peers) – Language.

One more marker mentioned from time to time by Italians has been clothing, which actually is connected mainly with moda (fashion): an inclination to follow trends and look fashionable.

| Clothing: total 7 times | |

| Follow fashion trends | 4 |

| Dress well | 2 |

| Dress different | 1 |

Table 15: Survey 2 (Italian peers) – Clothing.

Conclusion

As can be seen, personal behaviours are in the three cases the category that receives the most attention. It is probably indicating that as a category of markers composing the identity of a people, the social behaviour is the most evident one. Some differences do emerge however. While gestures and noise level (“they speak loudly”) were the aspects most commonly attributed to Italians in the first survey, previously unmentioned traits appear in the second, like the importance given to culture and the arts, to family, and to soccer. And those traits have a high rank in the importance given by Italians themselves. It is evident that the observations transform from a more superficial vision to one based on experience and familiarity with certain habits that are typical at least in the specific area where the students studied, though also in Italy as a whole. It is also interesting to note how the perception of food, another category that is present in both the first and second groups, radically changes form. While the first group expected mostly pizza and pasta eaters and obsessive coffee drinkers, the second group highlights how food in Italy is ‘experienced’, as well as simply consumed. One more time, this characteristic is recognized by Italians themselves. There are also much fewer observations related to physical traits, though remarks tied to fashion and elegance do remain. This could also be interpreted as a result of greater familiarity with the population, which results in attention being moved away from aesthetic factors and toward more behavioural and social aspects. A decline in the number of character-related descriptions can also be seen, which is perhaps an unconscious result of the awareness of the cultural context of certain social behaviors, ensuring that they are no longer perceived as a disposition but simply social and cultural constructs. To conclude, the survey achieves two objectives: on one side, quantitative data that highlights some traits that an outsider characterizes as being undoubtedly Italian (social behaviors, passion for food, attention to aesthetic appearance); on the other side, qualitative data that denotes a significant change in the observations of single categories between the first and second group. In all cases, the items and the rankings of the Americans who have been in Italy are closer to the Italians ones, more than the Americans who have not been here yet. It could thus be concluded that greater exposure to the ‘other’ entails more sharing and, as a result, understanding and knowledge.

Italian-ness: a social construct

Although we can see how the idea of Italian-ness becomes more similar to the one that is self-ascribed by Italian peers, one should still be careful in using that word. In Richard Jenkins words: “The internal project of the construction of a sense of shared similarity is no less significant than the construction of a sense of difference from external Others. The two are, of course, closely connected. And both are, definitively, constructions: they are utterly imagined” (Jenkins 2000: 10) This is more true when connecting ethnicity to the term of a nation or state: Italian-ness, just like any other ‘national-ness’. I support the view that institutions (States or Nations) promote the idea of ‘national-ness’ in order to create a sense of membership, linking citizens to some endorsed ‘cultural stuff’ that unite them. In Jenkins’s words: “construction of national identity is, after all, explicit projects of the state” (Jenkins 2008: 15). Even if a social construct, ethnicity is still something to deal with, as stated in the already cited quotation by Jenkins: “people orient their lives and actions in terms of it” (Jenkins 2000: 10). This assumption gives sense to my article: what is then the cultural stuff that marks Italian-ness in my study case group? At this point I would like to offer an interesting observation by Jean Cuisenier, which has been the guiding principle I have followed in the interpretation of Italian-ness: “[The ancient Greeks] taught that the ethnicity of a population, that which allows them to have a common identity, lays neither in the language nor territory nor religion nor in this or that aspect, but in the project and activities that bestow meaning to the language, the possession of a territory, the practice of customs and religious rites.” (Cuisenier 1994: 10) Although it may seem that Cuisenier is simply stating the constructionist approach according to which identity markers such as language[4], territory and religion serve as a matter of fact other purposes or ‘projects’, what Cuisenier is actually emphasizing is that rather than creating and focusing on boundaries, in a healthy society the establishment should raise interests in projects and instill the desire to work at some communal projects. The rest will come as a consequence.

The life changing experience

The participation into that project can be one of the goals of the Study Abroad programs, although at a limited extent. Generally students report that their study abroad experiences have been life-changing, and “they feel that they have changed in profound ways while they have been away” (Lindstone and Rueckert, 2007: 220). This life changing experience takes place in the context of Study Abroad Programs, which offer many opportunities for significant and transformative learning. That learning contributes to increase, and probably enhance, the students’ cultural capital: repeating Bourdieu’s definition, cultural capital is something that a person acquires for equipping oneself, for example forms of knowledge, skills, education and advantages that helps the individual to gain a higher social status in a society (Bourdieu 1986). Consequently, modern universities have a role in developing such capital in their graduates, and studying abroad plays a fundamental role in the current international mobile world.

Bibliography

- Bennet MJ (1998) Intercultural Communication: A Current Perspective”, in (Ed. by Bennett M. J.), Basic Concepts of Intercultural Communication: Selected Readings, Intercultural Press.

- Bourdieu P (1986) The Forms of Capital”, in Richardson, J., Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education. Greenwood;

- Cuisenier J (1994) Etnologia dell’Europa, Il Saggiatore;

- Institute of International Education: Open Doors Report 2017. www.iie.org, 2017;

- Jenkins R a. (2000). ‘The Limits of Identity: Ethnicity, Conflict and Politics’, Sheffield OnLine Papers in Social Research, no. 2 (Nov. 2000): http://www.shef.ac.uk/uni/academic/R-Z/socst/Shop/2.html b.(2008) Rethinking Ethnicity: Arguments and Explorations, Sage. (Second edition);

- Knopick R (2016) The Economics of Italy’s U.S. College Programs”, in Vista, vol. 27, Summer.

- Lindstone A, Rueckert C (2007) The Study Abroad Handbook, Palgrave MacMillan;

- Ricciardelli F (2017) Florence and Its Myth”, in (Ed. by P. Prebys & F. Ricciardelli), A Tale of Two Cities: Florence and Rome from the Grand Tour to Study Abroad, Edisai.

- Schneider PK (2013). Educating in Paradise: Fifty Years of Growth in Study Abroad in Italy. (Retrieved February 2, 2017, taken from

- https://www.aifsabroad.com/italy/