Traveling Habits of American Study Abroad Students Ph.D., M.A., Prof. Piero Ianniello*

University of New Haven, Italy

*Correspondence to: Piero Ianniello

Citation: Ianniello P (2023) Traveling Habits of American Study Abroad Students. Sci Academique 4(2): 83-98

Received: 16 September, 2023; Accepted: 04 October, 2023; Publication: 11 October, 2023

Abstract

Traveling for education among Americans has a long history that dates back to the 17th century. Currently, many Universities and Colleges have a study abroad program, in which students spend a brief period of time studying and being immersed in a foreign culture in order to enhance their personal growth. The personal growth is then generally considered enhanced by the experience of traveling by themselves. Through empirical research conducted on 76 American students enrolled in a Study Abroad Fall semester in Italy, corroborated by first-hand observation, this article aims at outlining the habits of traveling (outside the academic requirements). Additionally, it aims at understanding the students’ perception of the educational and experiential enrichment they received from traveling and how it affected their academic performance. The article concludes delineating the comfort zone within which students take their trips when studying abroad.

Keywords: Study Abroad in Italy; Travels; Educational learning; Experiential learning

Intro: Traveling for education

A comment made by a student: “I learned more about different cultures in Europe in general than if I just stayed in Italy”. Scholars generally agree that all travel is educational because it is able to broaden one’s individual mind through the experience (Schneider 2013; LaTorre 2011; Steves 2009).

The importance of travelling, in its various forms and significances, represents one of the primary elements of life in the modern world. Ricciardelli (2017: i) writes that even in pre-industrial era, people used to go on journeys and they did it so much more frequently than anyone can expect nowadays. In ancient societies, people traded goods, engaged in political and military activities by migrating from one place to another. For these reasons, roads were constructed by the ancient Roman Empire. The uprising of political boundaries, civilian conflicts, and the consequent lack of security, after the fall of the Roman Empire, led to a decrease in the number of people moving around.

People began to travel again during the second half of the Middle Age. This reached its maximum peak during Christopher Columbus’ expedition across the sea. In 1618, the Englishman Fynes Morysson published the main touring manual about travelling in Europe – aiming to assist people who wanted to explore Europe for pleasure. This initiated the concept of going around to other places as an open door for greater intellects. For nearly a century, American students have travelled abroad to engage in higher educational studies. Currently, with increased universal mobility, “[…] there has been a boost in the number of students participating in higher education [abroad]. Many universities now boast a robust semester abroad program.” (Armstrong and Harbon 2010).

Traveling abroad as a valuable experience for one’s own education ever since the XVII century, when, mostly in England, young members of rich families used to conclude their studies with a journey around Europe, usually joined by their private teacher (until the last century, academic education has been prerogative of upper classes). Those journeys generally lasted for a couple of years. Most of the time, an extended residence took place in predominant places for arts in Europe, Italy in particular. The goal was to build up a cultural and personal background, which was seen as essential for scholars.

In the course of nineteenth century, educational travel became a central element also in North American culture.

Study Abroad today

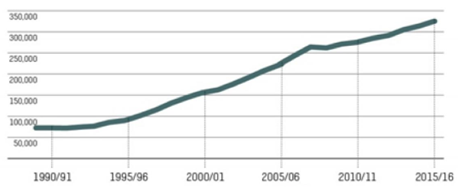

In American universities, Study Abroad programs represent a source of great pride because they are appreciated by students while also representing an attractive point for potential future students. According to an estimation provided by the Institute of International Education (IIE), more than 300.000 university students from the U.S. study abroad each year. In 2015/2016, 325.399 American students studied abroad, with an increase of 3.8% compared to the previous academic year (Open Doors 2017).

Figure 1: US Study Abroad Students 1989/90 – 2015/16. Statistics provided by IIE 2017.

American students attend 2.600 programs in 129 different countries. The most commonly attended destination for Study Abroad students is the UK, closely followed by Italy. Besides those traditional European destinations, recently

“[…] study abroad [is] emerging in Asia, South America, Africa, Oceania and Middle East, to the point that in the United States[,] universities offer their students the opportunity to choose a study abroad program virtually anywhere in the world” (Ricciardelli 2017: vii).

Studying abroad is also becoming more and more popular. In the words of Du Terroil and Santonino who studied the phenomenon naming it as an ‘industry’,

“Whereas at one time study abroad was for a certain “elite” type of student[,] it is increasingly becoming a vehicle for all students. Even still, only a relatively small percentage of students participate in the study abroad experience” (Du Terroil & Santonino 2012: 117).

In its Final Report, issued in 2005, the Abraham Lincoln Commission on Study Abroad Programs indicated as a goal to be achieved by Academic Year 2016-2017 the participation in study abroad of one million American students each year. It also, above all, at increasing the number of students enrolled in courses at the undergraduate level (Global Competence & National Needs ). This goal has proven to be too ambitious. Nevertheless, it shows the high interest in supporting study abroad experiences in the education process of American students. Between 2010 and 2011, the number of North American students who came to study in Europe reached 149.663 (Ricciardelli 2017).

The phenomenon is thus profitable to everyone: the students whose curriculum will make them more competitive in the job market, the educational institution which may boost a program abroad and become more attractive to students, the hosting communities where the Institutions decide to settle in, bringing with them a number of needs relating to lodging, eating, and shopping in which the locals are happy to respond to. The North American model of studying abroad, which is based on placing organized structures abroad, is rather expensive when compared to simply international students’ mobility, as it happens at the European level with the Erasmus Program, which is a student exchange program between European countries (Schneider 2013: 150). As shown by Thirty Years of History, Activities and Impact of North American College and University Programs in Italy, a report by AACUPI (Association of American College and University Programs in Italy), this American model “of an academic presence abroad is a historical anomaly, one which seems to have set an example only for Canada” (Prebys 2017: 19). Only recently some more countries are venturing in something similar, like the Australian Monash University in Prato. Hence the term ‘academic tourism’, to designate

“[…] any stays made in higher education institutions in places outside their usual environment for a period of less than one year, the main objective of which is to complete degree-level studies in universities and/or attending language courses organized by these centers” (Rodríguez et al. 2013: 1).

The phenomenon includes programs aiming to the mobility of students, such as Erasmus (European Region Action Scheme for the Mobility of University Students). As for the American students, this academic tourism refers to the period they spend in Study Abroad Programs (Schneider 2013: 4). The variety of North American student mobility programs ranges from academic stays to single language courses, internships and study trips to foreign higher education institutions (excursions, summer courses, research stays (Hopkins 1999: 38). As stated by the Institute of International Education (IIE), Italy is the second most popular destination for studying abroad after the UK and is the first choice out of non-Anglophone countries (According to the Association of American College and University Programs in Italy, students prefer traveling abroad within the confines of their mother tongue, rather than facing the change of the language they use). According to the Association of American College and University Programs (AACUPI), in 2011 30.361 students chose Italy for their study abroad experience (+ 8,7% increase compared to 2010). In the same year, 33.182 students chose UK as a destination, with a trend growing by 1,5%. In the academic year 2011-2012, American students opting for Italy increased by 8,0%. The Open Doors data, based on statistics furnished by home campuses about their study abroad programs for students from the United States studying in Italy, report even greater numbers, some 20% more than the 30.361 stated above (In technical terms, this is because the AACUPI does not count short programs, which are included in the total of students coming to Italy calculated by the Global Education offices of the home universities). The most recent statistics, provided by the IIE are as follows:

| Rank | Destination | 2013/14 | 2014/15 | % of total | % change |

| WORLD TOTAL | 304.467 | 313.415 | 100.0 | 2.9 | |

| 1 | United Kingdom | 38.250 | 38.189 | 12.2 | -0.2 |

| 2 | Italy | 31.166 | 33.768 | 10.8 | 8.3 |

| 3 | Spain | 26.949 | 28.325 | 9.0 | 5.1 |

| 4 | France | 17.597 | 18.198 | 5.8 | 3.4 |

| 5 | China | 13.763 | 12.790 | 4.1 | -7.1 |

| 6 | Germany | 10.377 | 11.010 | 3.5 | 6.1 |

| 7 | Ireland | 8.823 | 10.230 | 3.3 | 15.9 |

| 8 | Costa Rica | 8.578 | 9.305 | 3.0 | 8.5 |

| 9 | Australia | 8.369 | 8.810 | 2.8 | 5.3 |

| 10 | Japan | 5.978 | 6.053 | 1.9 | 1.3 |

Table 1: Destinations for studying abroad.

It is very likely that in a few years Italy will become the most preferred destination for students studying abroad, whereas it still seems to be the second choice for Anglophone speakers.

Besides school trips

When studying abroad, American students seem to like taking trips besides those organized and offered by the program. Travelling is recognized by all scholars (and those who work in the field) as one of the best ways to enrich the studying abroad experience.

“Their experience abroad, in fact, is enriched in this way: traveling throughout the country means not only visiting new places and admiring their attractions, but it also means knowing how to adapt oneself to transportation methods, interacting with new people and getting to know different local traditions” (Schneider 2013: 135).

Students also seem to appreciate the opportunity. According to a survey conducted by Istituto Regionale Programmazione Economica Toscana (IRPET), in the academic year 2012-2013, only 41,3% of the students’ answers connected the experience to an educational objective. Travelling around Europe and curiosity were the most popular answers.

| Answer** | Absolute Frequency | Bearing by % on the Whole Sample*** |

| I want to travel in Europe and in Italy | 928 | 72.6 |

| I was curious about experience abroad | 828 | 64.7 |

| I consider it an important experience for my education | 528 | 41.3 |

| I have particular interest in the artistic and cultural heritage of Italy | 520 | 40.7 |

| I consider it useful for my career | 333 | 26.0 |

| I came because of my Italian origin | 236 | 18.5 |

| I came to meet new people | 227 | 17.7 |

| I sought a change in my academic routine | 194 | 15.2 |

| Because other members of my family had the same experience | 115 | 9.0 |

| I followed the advice of my professors/academic staff | 86 | 6.7 |

| I followed the advice of my family | 80 | 6.3 |

Table 2: AACUPI, Schneider 2013.

One should distinguish between trips organized by the Institution and those taken by oneself. Schneider notes that 99% of North American students travel with their Study Abroad Programs (SAPs) in Italy for approximately 3.8 days. They travel by themselves in Italy for 14 days, and between 20-30 days within Europe. This coincides with the advent of the low cost flights, which connect the most popular destinations in Europe. Although on one hand travelling is recognized as having a positive impact on the personal growth of students, it might lower their academic engagement on the other hand. Consequently, Study Abroad Programs have to deal with it as a problem:

“In order to maintain a high level of academic performance, faculty and program directors try to limit access to frequent trips by offering alternative trips related to the curriculum. Often they take the students off the beaten path ‘slow mode’ transportation nearby destinations” (Schneider 2013: 37).

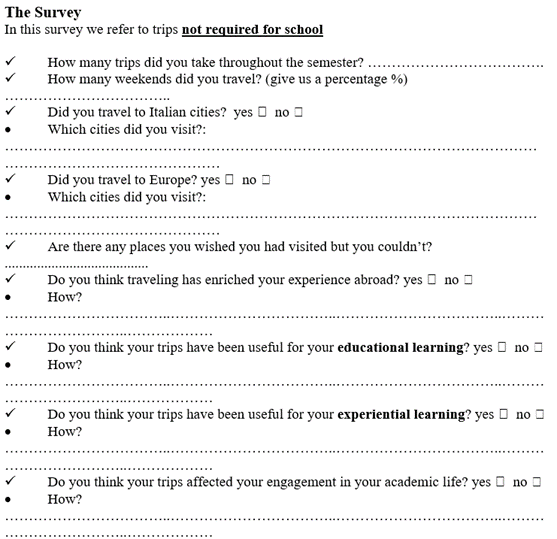

The survey

A group of 76 study abroad participants from an American Study Abroad Program settled in Tuscany, Italy were surveyed. Questions of the survey were carefully chosen for the purpose of the research. Attention has been paid to the appearance of the survey: concentrated on only one page, with little empty spaces, so that students would not feel overwhelmed filling it out.

I have opted for both open-ended and closed-ended questions. The latter, only yes/no questions in order to get the interviewees engaged with a first easy response and giving way then to an open-ended question which took them to a deeper reflection, without influencing respondents’ answers in any way (these kinds of questions are unbiased and do not show to respondents the possible expectations of what the researcher might be looking for). Respondents were asked to write, without prompt, how the traveling affected their experience abroad. After a general question (Do you think traveling has enriched your experience abroad? / How?), questions were detailed into educational (‘Do you think your trips were useful for your educational learning / How?’ and experiential learning (‘Do you think your trips were useful for your experiential learning / How?’). The final question investigates their academic engagement, a quality answer that predictably causes some difficulties to respondents because in a way they had to ‘evaluate’ their academic performance. This is also the reason behind the choice to place it at the end of the survey.

How much they travel

All students have been traveling during the semester. All travelled in Italy, whereas only 4 of them (out of 76) did not travel abroad (5.3%).

Students report the number of trips they took throughout the semester was an average of 9.7, and they have travelled the 57.9% of the available weekends spent in Italy. The semester they spent in Italy was composed of 15 weekends, including two weekends comprised for the semester break, (in which students might have taken more than one trip) and the first and the last weekends of the semester (in which students usually do not travel because they are tired and focusing on final exams).

Where they travel

Cities or places in Italy have been visited 254 times, whereas cities or countries outside Italy (all within Europe, with the only exception of Morocco) have been visited 367 times. An emblematic data, that reveals how Italy, as a Study Abroad location, is mainly a support base from which students throw themselves in trips to far destinations, outside of Italy. Vicinities (places in Tuscany without a high touristic appeal, but easily reachable by public transportation) have been visited by three students only. It is interesting to note how Rome, the most visited place in Italy, has been visited by 58 students (76,3%), whereas a similar number visited Germany (72,3%). The high number is probably due to the fact that the survey had been done in the Fall semester: almost all trips to Germany headed to Munchen, the throne of Oktoberfest.

Oktoberfest was far more appealing than Venice (35,7%) or even France (with Paris as the main destination: 44,7%). Only United Kingdom (with London as main destination) was able to compete with the high numbers recorded in Germany: 50,5%. This is confirming what ACUUPI says about American students who prefer traveling to English speaking countries. Due probably to the good weather with high temperature registered in Fall 2019 (it registered the warmest November in history), destinations to beach places were probably preferred to cities: Cinque Terre (60,5%), Viareggio (17,1%), Croatia (6,6%) and the Amalfi coast (including Naples and Pompeii: 47,3%). This last trip (usually an organized tour) was also one of the few to Southern Italy: only 17% of the trips to Italy headed to the South, 7,1% of the total).

As noticeable from the list, most of the trips are to highly touristic sites, destinations favoured by low cost transportations (mainly airplane). Each country seemed attractive for only one destination: Switzerland was visited by 29 students (38,1%), but except three of them who visited Geneva (because a UN conference, an academic requirement for one class), all the remaining 26 visited Interlaken (a renowned skiing resort). On the same line, all those who visited Netherlands, England or Portugal visited only Amsterdam, London and Lisbon. The same happened with France/Paris (with the exception of a few who went to Normandy, another requirement for a class) or Belgium/Bruxelles or Hungary/Prague. Only very few visited other cities, like in Dublin, they moved to the surrounding coast, or when in Germany, they visited Aushwitz (usually a tour package).

It is probably the short time for their visits that does not allow them to extend the exploration of their surroundings. Moreover, several students refer to ‘tours’, pre-organized tour packages with flights and hotels already booked by an English speaking tour operator, or in cases like Interlaken or Amalfi coast, bus trips leaving each weekend. Here is the list of the destinations:

| Italian destinations | Foreign destinations |

| – Rome (visited by 58 students out of 76, 76.3%) | – Germany (55 times, 72.3%) |

| – Cinque Terre (46 times, 60.5%) | – UK (46 times, 60.5%) |

| – Amalfi coast, Pompeii, Napoli, Capri, Positano (36 times, 47,4%) | – Ireland (35 times, 46,1%) |

| – Venice (27 times, 35.5%) | – France (34 times, 44.7%) |

| – Milan (19 times, 25%) | – Switzerland (29 times, 38.2%) |

| – Viareggio (13 times, 17.1%) | – Spain (25 times, 32.9%) |

| – Genova (7 times, 9.2%) | – Austria (25 times, 32.9%) |

| – Sirmione (7 times, 9.2%) | – Netherland (22 times, 28.9%) |

| – Verona (5 times, 6.6%) | – Hungary (19 times, 25%) |

| – Parma (4 times, 5.3%)* | – Belgium (16 times, 21.1%) |

| – Ravenna (3 times, 3.9%)* | – Poland (11 times, 14.5%) |

| – Bari (3 times, 3.9%) | – Greece (9 times, 11.8%) |

| – Vicinities (3 times, 3.9%) | – Portugal (7 times, 9.2%) |

| – Lake Garda (2 times, 2.6%) | – Scotland (5 times, 6.6%) |

| – Salerno (2 times, 2.6%) | – Sweden (5 times, 6.6%) |

| – Cortona (2 times, 2.6%) | – Croatia (5 times, 6.6%) |

| – Carrara (2 times, 2.6%)* | – Monaco (5 times, 6.6%) |

| – Polignano a Mare, Alberobello (2 times, 2.6%) | – Morocco (5 times, 6.6%)* |

| – Vinci (2 times, 2.6%)* | – Norway (4 times, 5.3%) |

| – Ferrara, Lake Como, Portofino, Maranello, Tramonti di Sopra, Arcidosso, Manciano, Arezzo, Trento, Gallicano nel Lazio/Latina, Palermo (1 time each, 1.3%) | – Denmark (3 times, 3.9%) |

| – Czech Republic (2 times, 2.6%) | |

| * Probable destinations for classes | * Only destination outside Europe |

Table 3: Survey – Destinations.

More wishes

Mostly all students wish to visit other locations. Only two of them answered ‘No’ to this question. One of these students did not travel abroad during the semester, the other one only visited Interlaken abroad, and Venice and Viareggio in Italy. It is possible that those students have a limited budget. With the exception of a few noticeable peculiarities, in general, the wish list of places is not far from the ones students already visited. As predictable, Rome does not compare in the list, and Germany has only a little mention: both places have already been visited. It is surprising how Sicily, which has been visited only one time, is in 5 students wish list. Also, Russia (3) and Romania (2) have multiple mentions in that list. Besides Venice, Sicily, Milan and Naples, there are no Italian places that students wish to visit, not even Tuscan ones. Here is the list:

- France: mentioned 16 times

- Greece: (14 times)

- Spain (13 times)

- Switzerland (11 times)

- Ireland (9 times)

- Croatia (7 times)

- Morocco, Venice (6 times each)

- Sicily (5 times)

- Scotland, Netherland, Poland (4 times each)

- Germany, Portugal, Russia, UK (3 times each)

- Naples, Milan, Romania, Hungary, Sweden, Denmark, Belgium (2 times each)

- Iceland, Ukraine, Wales, Norway, Austria, Czech Republic (1 time each)

Enriching the Study Abroad experience

Only one student out of 76 (1.3%) declared that traveling during the semester was not useful for enriching their experience abroad. The same student has also declared that his or her trips (several trips in Italy and in Europe) did not help with neither educational nor experiential learning.

The remaining 75 students (9.7%) instead consider that traveling boosted their study abroad experience. Reasons for this enrichment were the following:

- Enriched their Cultural Experience (mentioned 43 times: 57,3%). History and Art are included here.

- Made it Fun: made the experience more fun and allowed to visit places in their wish list. (mentioned 27 times, 36%).

- Improved Independence, Self-Confidence (18 times, 24%).

- Opportunity to Practice Italian or Learn a New Language (mentioned 4 times).

- Gave the Opportunity to Know New Food (mentioned 3 times).

From all that, it is clear that students appreciate the cultural side of the experience, but this does not exclude that the main reason for traveling is having fun or taking advantage from the chance: “I got to explore all these amazing places that would be difficult to visit when not in Europe”. Also: “The places I visited throughout my time here are places I’ve always wanted to go to. The fact that I was able to actually visit these places has made me so grateful for this experience”. Other comments on the same line were: “The city here is boring, so traveling made the experience fun”, and at the end of the experience: “I have a lot of stories”. The limited cultural acquisition is also corroborated by the sojourn time (generally around 1.5 days for each city they visit). A student wrote: “Even though for a very short time, traveling gave me the opportunity to know other cultures”. Actually, the immersion in different cultures seems to be more an ambition (or even an illusion) than an effective acquisition. Only 18,5% of the students recognized that the enrichment involved a personal sphere, which enhanced personal maturity: “Made me have more responsibility on my own”. Practicing Italian, which is one of the subjects studied at school, is relegated at 4%, and the tasting of different foods is at 3%.

Educational learning

From 76 surveys, only 7 students (9%) declared that trips were useless for their educational learning. Although the questions specifically asked them to explain how it was useful, students seem unable to explain how they improved their academic performance. Many of the answers were (as a kind) a generic “[Trips] allowed me to apply what I learned in my classes to real life scenario”, or “Traveling allowed me to connect what I learned in the classroom to actual places”. One more answer I want to report is: “Most of our education was tied to traveling, so it was very beneficial”. This last student has probably confused the trips taken by him/herself and the field trips provided by the institution. In general, it seems that students have some difficulty in defining their educational learning. Classes were mentioned only 14 times (18,4%), whereas many other answers have been a generic ‘experience different cultures’, without being able to give more information about how the mentioned ‘experience’ had affected their educational learning: “Seeing different people/cultures/way of life broadened my world view + helped me put things I learned into context.” Those who instead were able to detail the answer (53,6%, of those who answered yes), have answered in the following way:

- Useful because visited museums and learned about history (35,1%)

- Useful to improve Italian language skills (learned in class) (29,7%)

- Useful for comparing different cities/countries (13,5%)

- Useful for learning with foreign languages (8,1%)

- Useful for comparing health systems (5,4%)

- Useful for connection with Art class (5,4%)

- Useful for connection with Food class (2,7%)

Visiting museums might understandably be a good way to improve general knowledge and understanding that might be connected to different classes. No students actually mentioned the art or history class, all of them seem to refer a general personal growth. In the words of a student, “I went to many museums and I was able to immerse myself in history in order to better understand the world”. It is surprising how the improvement of the Italian language is mentioned by almost one third of the students who found traveling useful for their learning. That aspect was mentioned only by 4 students as an enrichment of the experience abroad. This is probably due to the fact that the Italian class is a requirement for the students object of the research, so Italian language is not important as a cultural aspect, but it is a class and students feel that trips around Italy helped the learning. As said above, trips seem to have a very limited impact on the classes: only art class was mentioned twice and food class mentioned once. This data is even more astonishing if one remembers that those students have taken the Study Abroad program in Italy, renowned for its art and food. In general, besides visiting museums and a general cultural experience, which might affect the overall learning, there is very little explanation of how the trips affected the educational learning of the students.

Experiential learning

73 students out of 76 (96%) declared that traveling was important for their experiential learning. Only 3 did not recognize any importance. Nevertheless, one student explained that “We unfortunately didn’t get too much hands-on experience but I certainly learned how to be socially aware: how to travel”. One more time, students were not able to clearly distinguish what exactly improved their experience: “I am not really sure, but it did”, this is how one student expressed it. This is the list of their answers:

- Useful to know different cultures and lifestyles (31,6%)

- Useful for personal growth, independence and self-confidence (13,3%)

- Useful for improving communication skills (11,6%)

- Useful for learning how to plan trips (10%)

- Useful for improving problem solving skills (10%)

- Useful for broaden the perception of the world (6,6%)

- Useful as a general cultural experience (5%)

- Useful for its connection to the class learning (5%)

- Useful for improving team working skills (3,3%)

- Useful for tasting new foods (3,3%)

- Other aspects (mentioned only 1 time): 0,3%

I tried to regroup the answers referring to experiencing different cultures and ways of life, which has been, once again, the most mentioned aspect. Here, it must be noted, students used several different verbs to express their experiences: to know, to see, to put hand in, to understand, to embrace, to show. “I got to see how other people live and I became more open-minded” or “Traveling a lot makes you embrace cultural differences by jumping right in”. Personal growth was the second most mentioned aspect. It sometimes was hard to regroup several disparate answers, so I regrouped all those who were in some way related to personal, including the acquisition of self-confidence and independence: “Taught me things about myself and the world that a class couldn’t” and “It made me more comfortable being in unfamiliar places”. It is possible that other aspects, such as the improvement of the communication and of problem solving skills might be included in personal growth. I have preferred to leave them in a separate entry because they were specifically mentioned (whereas personal growth was a more general feature). In this case, personal growth would be the most mentioned feature.

Trips and academic life This question was highly divisive. 19 students (25%) answered that the trips they took did not affect their academic life, whereas the 75% said it affected it. It is important to note that not all those who answered yes gave a negative meaning.

Answers have been:

No: 19 times (25%)

- I could manage my time and my work (4 times)

Yes: 57 times (75%)

- Had to manage/hard to manage (13 times, 21,6% of the mentions)

- More engaged/more interested in academics (11 times, 18,3%)

- Academics lowered/less engagement (10 times, 16,6%)

- Tiredness (7 times, 11,6%)

- Improved connection to classes (6 times, 10%)

- More culturally aware (3 times, 5%)

- Ignored homework (3 times, 5%)

- Conflicted with classes (3 times, 5%)

- Less time for studying (2 times, 3.3%)

- Missed classes (2 times, 3,3%)

I can include ‘More engaged/more interested in academics’, ‘Improved connection to classes’ and ‘More culturally aware’ entries among the positive meaning students gave to their answers. The answer ‘No’ also has a positive meaning (Trips did not affect their academics, which was same as at the home campus). Adding the ‘No’s (19 times) to ‘Yes’ in a positive meaning (20 times) the result is 39, which is 49,3% of the entries. The negative meaning was recognized by 50.7% of the students. A perfect balance, which can be read as a big confusion among the group, unable to define if trips were actually affecting their engagement. Answers were varied. In several cases, students showed a sort of confusion about the academic that the survey was questioning: “Traveling made me want to learn more about other countries”. Probably this student is confusing what academic is (I doubt he or she took or will take a class about European countries culture). The most precise answers were those about the negative effect of trips: “My travels only had a negative effect on my education, as I had less time to study” or “Going to class four days a week Monday-Thursday and then traveling Thursday night to Sunday made it challenging to keep up with assignments. Wish I took easier courses when coming abroad”. Nevertheless, students found that it was worth it anyways: “It affected it because I travelled so much that I could not focus as much on school work. I know this was a once in a lifetime experience so I wanted to take advantage of it”.

In some cases, it seemed that academics were ‘disturbing’ travels: “Less engagement in academics because we had too much work while we were trying to travel”. Also, in the following case, it seems that their academic load is what pushes them to travel: “The course load was overwhelming and then you’re being pressured to travel”. Students who recognized an improvement of their engagement or of their interest in academics found it hard to define how. General answers were “Seeing other cultures improved my education”. Alternatively, even “I became more culturally aware and I can use this for career goal”. Some of them mentioned that traveling eased stress: “Having the time and opportunity to travel has actually helped with stress and made me more able to perform better academically”. It is possible, though, that some students included field trips organized by the institutions, including those for classes. This might be the meaning of an answer like: “Being able to apply things I learned/observed while traveling into my academic curriculum made me more interested to learn” or “Seeing the places we learned about in class enhanced my learning experience”. In the following case it is even clearer: “When in the food and cuisine class those trips helped me engage in what we were learning in the class”. In conclusion, the most representative answer by students seems to be: “Of course it made it harder to do homework/study, but most definitely worth it! Time management”.

Conclusion

In conclusion, according to the portrayal depicted by the students themselves, when abroad, American students travel a lot, and they travel to highly touristic destinations (mass-tourism) for a very short time. Traveling abroad contributes to the knowledge of different cultures, which gives way to personal growth (independence and self-confidence), but it partly affects the academic side. It is still to be clarified what the impact is on the academic side. If trips organized by the SAP are to popular places (for example: Florence, Siena, Lucca, Pisa, Pistoia, Prato) which are also art and historical cities, trips taken independently seem to be very far from any academic interest. Students often report their visits were to squares, sightseeing sites, buildings, rarely museums and most often, to pubs. If the educational learning is something that must be further investigated (probably with interviews rather than surveys), the experiential learning is something that certainly improved, thanks to the independent way they could travel. One more time, though, it is still limited by the choice of very popular places to visit. There might be several reasons behind the choice of these destinations. First, those places are well-renowned all over the world, so they sound appealing. Secondly, reaching those places is far less expensive than others. Plane fares are lower, and this is far more convenient to young adults. It must be noted that in their open answers, students often referred to ‘tours’, prearranged by English speaking agencies in which no reservations or organization is needed. This makes it possible to optimize the time and reduces the risk to do anything wrong, but on the other hand, it reduces the exposition to the foreign culture (language, habits).

Places they visit are English-speaking (UK, Ireland) or touristic seats where English is widely spoken. A student reported: “You step out of your comfort zone each time you travel which is a good thing”. This reflection might be true in any case, just like the overall experience of traveling abroad. As a general conclusion, though, the ways and the places where they travel seem to represent a sort of extension of their comfort zone. This is might be the reason why even Italian destinations are the same mass-tourism ones, despite many students taking an Italian culture class (which are supposed to stimulate the interest for the local context). Moreover, many students have Italian origins (and sometimes still in touch with family members) but hardly anyone takes on the adventure of visiting the towns from which their family moved from to the U.S.

Note: Limits

Just like in any qualitative research, mine may have some unavoidable limitations. When filling in the survey, it is very likely that students included destinations visited with the academic institution, despite the survey clearly stating: “In this survey we refer to trips not required for classes”. Together with an indeterminable margin of error made by students, this must be the reason why the overall number of visits stated by students (757) does not match the detail of their trips (amounting to 621). Destinations certainly visited for classes or within the institutional organization (such as Bologna, Siena, Lucca, San Gimignano, Pisa, Carmignano), have not been included in the count.

A final notation is about the subtle feeling coming when reading the answers of students, especially the last one that asked them to identify how their academic life was affected by trips: students seemed to justify their trips and tended to hide how much they (the fun side of the experience abroad) affected the academic side. This is only a sensation, though. It would be good to cross-reference students’ reports with the perception from teachers (visiting professors, above all, since they can compare the academic performance when studying abroad with the standards at the home campus).

About author: I am a full time professor of Italian culture and language at the University of New Haven, Study Abroad program in Italy. I graduated in foreign languages and literature (English and French) at the University of Florence and I received a II level Master’s degree in teaching Italian language and culture to foreign students. I gained my Ph.D. at the University of Antwerp. My research interest focuses on performing Italian-ness in educational contexts.

Bibliography

- Armstrong AC, Harbon L (2010) Developing Social and Cultural Capital through Semesters Abroad”, in Peter L. Jeffery, Professional Resources Services, Australian Association for Research in Education (2009 Conference Papers Collection).

- Commission on Abraham Lincoln Study Abroad Fellowship Program. (2005) Global Competence & National Needs: One Million Americans Studying Abroad.

- Du Terroil RM, Santonino III MD (2012) The American Study Abroad Industry In Italy”, International Journal of Arts & Sciences, No. 5.

- Hopkins J. Roy (1999) Studying Abroad as a Form of Experiential Education.” Liberal Education, no. 85.

- Institute of International Education (2017), Open Doors Report 2017.

- LaTorre E (2011) Lifelong Learning through Travel”. Delta Kappa Gamma Bulletin: 78.

- Prebys P (2017) (Ed. by). Thirty Years of History, Activities and Impact of North American College and University Programs in Italy.

- Ricciardelli F (2017) Introduction”, in (Ed. by P. Prebys & F. Ricciardelli). A Tale of Two Cities: Florence and Rome from the Grand Tour to Study Abroad, Edisai.

- Rodríguez XA, Martínez-Roget F, Pawlowska E (2013) Academic Tourism: A More Sustainable Tourism”, Regional and Sectoral Economic Studies vol. 13-2.

- Schneider PK (2013) Educating in Paradise: Fifty Years of Growth in Study Abroad in Italy.

- Steves R (2009) Travel as a Political Act. Nation Books.

Appendix